Paul Amar, “Middle East Masculinity Studies: Discourses of ‘Men in Crisis,’ Industries of Gender in Revolution,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 7.3 (Fall 2011): 36-71.

Jadaliyya: What made you write this article?

Paul Amar: I began drafting this article two years ago in order to seek ways out of the impasse in which the study of sexuality in the Middle East had become trapped. I was asking myself, how do we highlight aspects of coloniality, geopolitics, and power in the study of sexuality, without, on the one hand, reducing the social subjects of sexuality to the dupes, tools, or incitements of Empire or, on the other hand, celebrating “sexual minority identities” as the harbingers of emancipation or modernization? I felt both kinds of reductivism mirrored rather than challenged the legacies of domination, impoverishing the complexity of social history, the contentious nature of politics, and the creativity of culture.

In this first phase of the drafting, my aim was to journey outside the box of Arab and postcolonial studies to survey the state of sexuality research in the fields of Latin American studies, public health, feminist International Relations, and critical military/police/security studies. I regularly engage these domains. I hoped to assemble from these fields a toolbox for graduate students, activists, and sexuality policymakers who were thinking about sexuality in the Middle East, but who had been stymied by the epistemological-political impasse.

As I was completing the first draft of this piece in early 2010, I became aware of an epochal shift taking place in the gender discourses and policy priorities of NGOs, public health bodies, humanitarian interventions, and security institutions in and around the Middle East. In the early 2000s, the issues of “homosexual identity,” “sex trafficking,” and, of course, female piety/religiosity had dominated the concerns of these organizations. But by 2009, a constant and consistent problematization of “masculinity” had become a central preoccupation, nearly overwhelming all others: masculinity dysfunctions caused by the “marriage crisis” and joblessness; predatory masculinity driving an epidemic of “sexual harassment”; authoritarian masculinity as the spirit of repressive militarism and police violence; atavistic masculinity as a cause of religious “extremism,” etc.

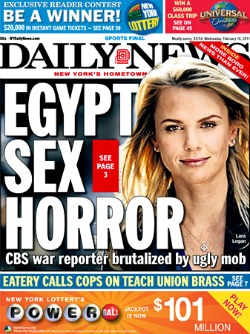

So in the second phase of writing this article, I decided to revise the piece to expose and shed critical light on this “masculinity turn” in the discourse of global governance and local government, and in the practice of international gender industries. Then, as I entered the third and final stage of rewriting this piece, incorporating the helpful suggestions of reviewers and of the journal and issue editors, the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions erupted. Instantly, global and regional press and government bodies read these uprisings as the effect of these newly ascendant, trendy forms of “masculinity crisis” that I had been mapping. So the final draft of this piece opens with the voices of these “masculinity specters” of the Arab Spring.

["Instantly, global and regional press and government bodies read these uprisings as the effect of these newly

ascendant, trendy forms of `masculinity crisis` that I had been mapping." Images via Google Images.]

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does it address?

PA: In its final form this piece still maintains its original objectives. It critiques a contemporary set of power formations around sexuality in the Middle East (as they comprise the current “masculinity industry”). And it serves as a tool-box of critical thinking methods that include:

a. studies of sexuality coming out of the Latin American-centered world-systems and dependency schools (which have a distinct view of the sexuality subject of modernity than do the post-colonial or subaltern studies schools),

b. new methods of studying sexuality coming from public health, ethnography, and performance studies that focus on sensory experience and embodied contact rather than on language and identity politics,

c. feministpolitical-science critiques of the masculinism (including the “female masculinities”) of new security regimes and humanitarian warfare, and

d. the return of biological determinism, which I have found has made an imprint on Middle Eastern literature and NGO discourse and not just on gene science and criminology.

I also do a brief review of the best of the new literature coming out on sexualities and masculinities in the Middle East, and how this new generation of scholarship has framed debates around liberalism, humanism, identity, and respectability. So the piece is a bit dense, to put it lightly!

[Paul Amar. Image provided by the author.]

J: How does this work connect to and/or depart from your previous research and writing?

PA: This work represents not so much a departure from my previous teaching and writing, but a moment of assessment. I have worked on police reform and paramilitary decommissioning for United Nations projects, on queer/trans/racial justice public policy for NGOs in Brazil, on prison reform/abolition in the United States, on sex work and AIDS justice transnationally, and on gender, politics, state theory, and globalization studies in the Middle East. So I have had to switch epistemologies, languages, fields of study, and research agendas dramatically throughout the years. But I have always felt that there were dynamic continuities and cross-fertilizations between the fields and agendas that would merit mapping out on paper. So this article gave me a chance to do this. And I am so grateful that issue editors Lara Deeb and Dina Al-Kassim, previous journal editors Sondra Hale and Nancy Gallagher, current editor Marcia Inhorn and managing editor Bonnie Rose Schulman, and the anonymous peer reviewers all who encouraged and supported this nutty plan of mine. They provided invaluable feedback during the process, along with a dozen other friends and colleagues, Omnia El Shakry and Terrell Carver in particular, who got roped into reading drafts of this, improving it substantially.

J: Who do you hope will read this article, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

PA: I hope that this article will be useful to activists, policymakers, and NGOs working on issues of gender, state violence, sexuality rights, and class justice, and to graduate students and academic researchers who are seeking new avenues for shedding light on these types of questions. I also hope that some of these critiques and perspectives make their way into the public sphere, so that journalists and the broader public come to think more critically about how notions masculinity and “Arab sexuality” unconsciously shape their view of the Arab Spring and of the recent uprisings, revolutions, humanitarian wars, and police actions in the region.

[Images via Google Images.]

Excerpt from "Middle East Masculinity Studies: Discourses of `Men in Crisis,` Industries of Gender in Revolution" [the following paragraphs are taken from pages 43-44 of the article, available at the link below]:

In the state and public sphere of many twenty-first-century Middle Eastern countries (particularly in Egypt, Morocco, Turkey, and Jordan) neoliberal market-making has been subsumed by particular kinds of humanism, blending a depoliticized form of Islamic moralism with contradictory forms of humanized police and military security-state enforcements. These humanized forms of control are designed to appear blind to or cleansed of class distinctions and ethnic difference, but are increasingly obsessed with sexualized gender and a privatized and securitized ethics of the self. In the Middle East, a new mode of governance, increasingly referred to as human security, works to blend hybrid forms of Islamic feminism and secular social hygiene projects. The current moment of securitized governance in the Middle East focuses on gender trouble and on disruptive public sexualities that have come to displace and repress the political visibility of how this governance form radically reinscribes class (into hygiene subjects), religiosity (into moralistic dilemmas), and race/ethnicity (into vectors of trafficking and perversion). In this context, a “human security state”[1] is one that blends increasing police and repressive power with highly gendered logics of militarized rescue, coercive social reform, and humanitarian intervention, which are seen simultaneously to justify and humanize the increasing intervention and surveillance power of the security model.

These new late-neoliberal or post-neoliberal gender industries have been generated in Middle East states as responses to the dysfunctions of market deregulation and privatization politics and the contradictions of neoconservative doctrine. They have also been generated in the wake of the de-radicalization of Islamism through its incorporation into middle-class moral reform movements and consumer cultures.[2] Projects for gendered public morality, sexual regulation, family constitution, and suppression of trafficking in bodies have become central axes of governance, executed through an unaccountable jumble of non-governmental organizations, government projects, municipal police, planning and public health initiatives, and international human rights and humanitarian organizations.[3] At the center of this new humanized security model, the governance formations identified above (security masculinities, paternafare/therapeutic masculinities, and workerist masculinities) build upon both colonial legacies and new discourses of security politics and the governance logics promoted by the mix of nationalism and neoconservative moralism.

In this context, can we assert that the discursive field representing Middle East masculinities is in crisis? This seems apparent, given the impasse in the debates between two camps. On one hand, there are those, often termed liberals or universalists, who focus on the heteronormative masculinity of the modern state while highlighting the resistance of women and queer subjects.[4] On the other hand, there are the anti-imperialists, who emphasize the forms of domination and exclusion that some forms of queer liberalism and feminist universalism reproduce.[5] The division of labor between the two methodological camps tends to reproduce the split between those who see masculinity as the crisis-node of sexuality, which, in turn, becomes a vector of imposition, and those who frame the sphere as a realm of performative autonomy. This binary often reanimates the dualism of West versus East, implying that a realm of sexuality is a driving force of modernity, with some focusing on its power to incite and dominate and others underlining sexuality as a realm of eroticized autonomy and emancipation. However, there are other, more productive approaches that identify sexuality as a realm of mechanisms by which domination and autonomy are simultaneously linked while appearing essentially distinct. This happens through the governance practices that generate fear and desire and that animate or degrade bodies and spaces.

[1] Paul Amar, The Security Archipelago: Human-Security States, Sexuality Politics and the End of Neoliberalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[2] Asef Bayat, Making Islam Democratic: Social Movements and the Post-Islamic Turn (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2007).

[3] Amar, The Security Archipelago.

[4] Afdhere Jama, Illegal Citizens: Queer Lives in the Muslim World (Salaam Press, 2008); Brian Whitaker, Unspeakable Love: Gay and Lesbian Life in the Middle East (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

[5] Joseph Massad, Desiring Arabs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[Excerpted from "Middle East Masculinity Studies: Discourses of `Men in Crisis,` Industries of Gender in Revolution," in Journal of Middle East Women`s Studies Vol. 7 No. 3 (Fall 2011). Copyright © 2011 by Association for Middle East Women’s Studies. Reprinted with the permission of Indiana University Press. The full text can be viewed and downloaded here.]